Melk Abbey

„Ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus” – That in all things, God may be glorified

Magnificent Sacral Building in Spectacular Setting

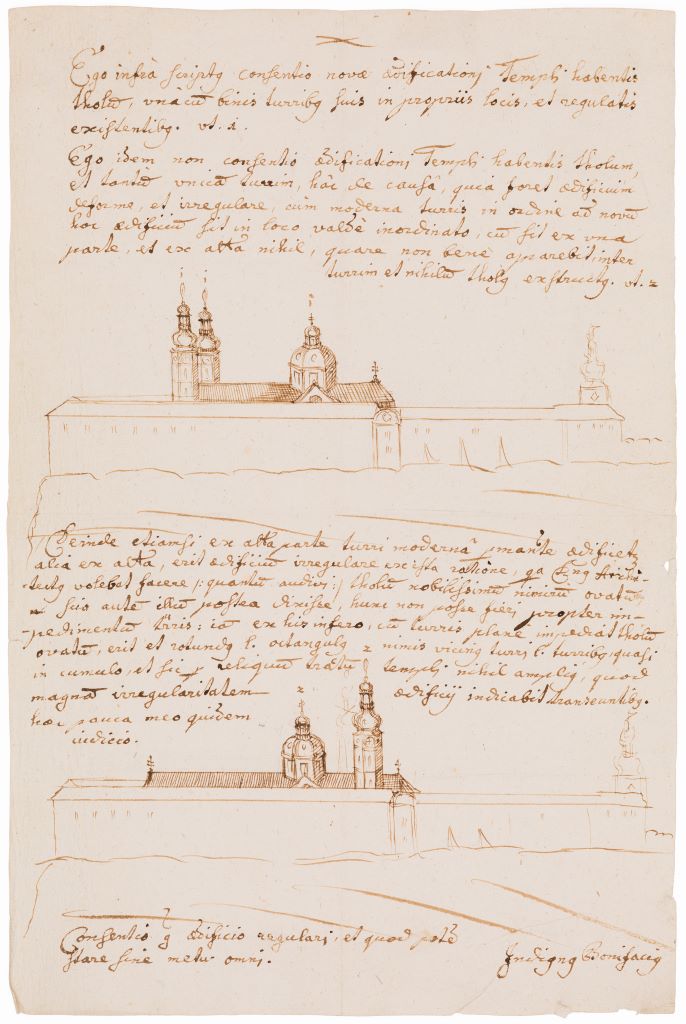

More or less in the middle between Vienna and Linz, a fascinating Baroque building sits on a granite rock overlooking the Danube, visible from afar like a fortress: Melk Abbey. From a distance one can already see the dome of the abbey church and the two towers, with golden ornaments, which look like hands raised towards the sky: the magnificent structure is clearly a sacral building and not a secular palace.

Melk abbey is one of the most impressive Baroque ensembles north of the Alps and plays an important role in the history of early Austria.

“The beautiful thing about Melk abbey is that the monastery is not only a museum, not only a school, not only an art-historically interesting building, but that life is stirring here in every hallway, in every room and there is constant motion. Motion is a prerequisite for life.” Father Martin Rotheneder

HISTORY MELK ABBEY

In 976 Otto II gave the Eastern March as a fief to the Babenberg family to secure the borders of his empire towards the East. The Babenbergs succeeded in expanding and securing the march towards the North and East. In the Eastern March there were several fortified centers which constituted military, spiritual and economic centers and offered protection to the populace. In the fortress of Melk, the Babenbergs already had a spiritual community of canons regular.

When Melk lost some of its importance due to the expansion of the march towards the East, Leopold II decided to convert the fortress into a monastery. At that time Saint Coloman, the patron saint of the march, and some of Austria’s first rulers – the margraves Henry I, Adalbert, and Ernst – had already been buried in Melk. Leopold II brought Benedictines monks from Lambach in Upper Austria to Melk so that they would pray at the grave of the Babenberg family and continue the work to establish Melk as a spiritual center of the region.

On March 21, 1089 the Austrian margrave Leopold II of Babenberg (1075-1095) gave the church and the fortress on the rock of Melk to the first Benedictine abbot Sigibold and his monks. Ever since, monks have been living in Melk abbey, without interruption, following the rule of Saint Benedict. In Melk abbey’s library there is still the rule book which the first monks brought from their original monastery, a manuscript which is now over 1000 years old.

Despite some external difficulties the monastery prospered. The annals of the monastery and the Melk Song of the Virgin Mary survived the terrible fire of 1297 and testify to the monks’ activity at that time. The abbey had a scriptorium, and the monastery school for choir-boys dates back as far as 1160.

“The transience of Creation, and particularly human failure, intransigence and one-sided problem solving create again and again times when important achievements crumble and great possibilities are not taken advantage of.

The Renaissance and Humanism period as well as the Reformation show how powerful intellectual movements and significant motive forces can open up great opportunities and release wonderful cultural and intellectual impulses, but how they can also make human shortcomings and bias perceptible. And just like History, every life has its ups and downs.”

Abbot em. Dr. Burkhard Ellegast OSB, excerpt from “Das Stift Melk” (“Melk Abbey”)

14th and 15th century ǀ Council of Constance

The 14th century was marked by the decline of the Church. Natural disasters, a plague epidemic, the Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism were symptoms of its demise. It was high time for a reform. The Council of Constance (1414-1418) may have rehabilitated the Church as an institution, so that there was again only one pope, but the desired reform of the Church didn’t happen. However, the call for a reform awakened forces which generated important intellectual and cultural achievements. As a result of the Council of Constance the monasteries were given the task of reforming monasticism, with Melk becoming a center of that reform. The Melk Reform was the basis of a restructuring of the monasteries in Austria and Southern Germany. Through its connection with the University of Vienna Melk abbey soon became a monastic cultural center – a “model monastery”. Many theological, monastic, and scientific texts were then written in Melk. About two thirds of the manuscripts in Melk abbey library come from that time. But in spite of this monastic highpoint there was no economic growth. The territorial sovereigns made great financial demands on the monasteries, and abbots were pulled into quarrels between the ruling prince and the nobility. Despite these adverse external circumstances, the reconstructed and remodeled abbey church was consecrated in 1429 and later decorated with a panel altar by Jörg Breu the Elder.

Protestant Reformation

At the beginning of the 16th century, there was another low point in the abbey’s history. Martin Luther’s reformatory ideas spread rapidly throughout Austria, and monastic life almost came to a standstill. Only three priests, three clerics and two lay brothers remained in Melk abbey. The ruling prince appointed secular officials to manage the monastery, resulting in many quarrels between the monks and the officials. The wars against the Turks led to higher taxes, and the abbey’s property around Vienna was devastated, so that the existence of the monastery was threatened. The upswing brought about by the Melk Reform had been completely negated.

Counter-Reformation

At the behest of the ruling family the Council of Trent resulted in the Counter-Reformation. Soon the unity of faith was restored, and the groundwork for a new upswing in abbey history was laid. Many well educated and religiously instructed young men from Germany joined the monastic community of Melk. The abbey school was renewed, as well as the theological education of the monks. Melk became once again a well-ordered monastic community.

“The interior recovery of the monastic community in the 17th century was soon reflected externally by the Baroque reconstruction of the abbey complex. A powerful sense of optimism prevailed in Austria at that time. The Turkish danger had been averted, and the economic upswing and especially the secured freedom of faith made people want to express their joy of living and newly acquired safety in faith.”

Abbot em. Dr. Burkhard Ellegast OSB, excerpt from “Das Stift Melk” (“Melk Abbey”)

The Baroque Period

Berthold Dietmayr (born in 1670) was elected abbot of Melk abbey in 1700. With the energy of his youth, his determination, and his intellectual agility Dietmayr proceeded with the necessary renovation work which resulted in a complete reconstruction of the monastery complex. Abbot Dietmayr found a congenial partner in the master builder Jakob Prandtauer, and renowned artists were chosen to create the interior decoration (among others Antonio Beduzzi, Johann Michael Rottmayr, Paul Troger, Lorenzo Mattielli). In 1738 a fire broke out which destroyed parts of the monastery and the church towers. This was a heavy blow to abbot Dietmayr’s efforts. He died in 1739. His successors completed the Baroque reconstruction.

Scientific Progress

In addition to the progress in the construction, scientific and cultural life also blossomed in the monastery. Historians like Anselm Schramb, Philibert Hueber, and the brothers Pez or the musicians Robert Kimmerling, Marian Paradeiser, and Johann Georg Albrechtsberger were famous well beyond the walls of Melk abbey.

Abbot Berthold Dietmayr was held in high esteem at court and at the Lower Austrian Estates. In 1706 he was appointed rector of the University of Vienna and in 1728 he became Privy Councillor of the emperor.

Close to God

People in the Baroque age had this deep, almost earthy faith, so they brought the unapproachable God down to Earth and built him magnificent audience halls for which nothing could be beautiful or splendid enough. But they did not only know of splendor and the joys of human life, but were also conscious of the downside: suffering and misery, disease and death. So they brought God to Earth and had something to hold on to. Religious processions, pilgrimages, penances, or veneration of relics were people’s efforts to be particularly close to God.

“Already under the rule of Maria Theresia, a deeply pious and devout woman, many new ideas had taken hold. Her ministers already acted frequently in the spirit of Enlightenment. After Maria Theresia’s death, when her son Joseph II began to rule, the spell was broken: with a vengeance, the ideas of the Enlightenment began to determine every aspect of the State and also its relationship with the Church. Many monasteries were dissolved; pilgrimages and religious processions were abolished; activities associated with feeling and emotion were limited. Everything was supposed to happen in the name of Reason.”

Abbot em. Dr. Burkhard Ellegast OSB, excerpt from “Das Stift Melk“ (“Melk Abbey”)

The Time after Maria Theresia

State decrees deeply affected the life in the monastery. Numerous parishes were assigned to Melk abbey as a result of Joseph’s parish reforms, which put a strain on the monastery’s economic and personnel situation. In the new parishes rectories and schools needed to be built and maintained. However, since Melk abbey fulfilled an important duty for the State by providing pastoral care for parishes, it was spared the fate of dissolution.

In 1783 the theological institute in Melk abbey was closed by imperial decree. Young theologians could then only be educated at the Viennese General Seminary, where clerics were taught entirely in the spirit of the Enlightenment. After their studies they came back to their monasteries and often changed the old ways. As of 1769 the new ideas also began to penetrate into the thus far cloistered monastic community of Melk abbey. The government appointed a commendatory abbot to run the monastery’s business operations, whereas the monastic community could elect an “imperial prior” for a 3-year-term to supervise spiritual life.

In 1787 the abbey school was relocated from Melk to St. Pölten, but the monastery was still responsible for the expenses.

New Autonomy

After Joseph II’s death some of the regulations were rescinded and under the rule of Emperor Leopold II (1790-1792) the monasteries regained their autonomy. Clerics again studied in the monasteries. In 1804 the abbey school returned to Melk. In the 19th century the Napoleonic Wars and Joseph’s parish reform caused an immense financial burden. For a long time, the Josephian mentality was still perceptible in the monasteries. Only in the 20th century new approaches rebalanced reason and faith.

“One-sidedness brings confusion and destruction and ultimately causes painful events which are hard to understand. Sometimes bitter experiences and a long time in-between are necessary that a low becomes a high again. If we lose sight of the big picture and of the individual, human life will always be threatened.”

Abbot em. Dr. Burkhard Ellegast OSB, excerpt from “Das Stift Melk” (“Melk Abbey”)

Melk Abbey in the 20th Century

The two world wars shook Europe to its very foundations. Often faith was driven back. A secularization of the way of thinking which ultimately rejects every higher power and doesn’t know responsibility towards God anymore resulted in terrible killing and murdering, in marginalization and abuse of power.

Despite everything and everyone the monasteries continued praying, tried to provide security and help, and walk a clear path of togetherness and faith.

During and after World War I it was possible, in spite of great difficulties, to install sewers, new plumbing and electricity in the monastery. Urgently needed restoration works could only be financed through the sale of cultural assets (e.g. a Gutenberg Bible).

As of 1938 Melk abbey was in constant danger of being dissolved, and monks were threatened with arrest. Many brothers were drafted. Property was dispossessed, the school was taken away from the Benedictines and rooms were confiscated. Only a small part of the building could be used as a monastery. Because of the abbey’s continued existence, it could better survive the last days of the war and the period of the occupation, which resulted in tremendous damage to dissolved monasteries.

Post-War Period

After the two world wars the abbeys tried to bring the monastic spirit back. The war and the ban on accepting new monks at that time left substantial voids. Abbot Maurus, whose strength lay in pastoral care, was able to deal with these problems and set a Church-conscious, priestly course. School, parishes and abbey should all be provided for equally. The badly damaged dome of the church was repaired, and the long overdue exterior restoration started.

In 1960 Melk abbey was open to tourists for the first time, and the exhibition about Baroque style brought 380.000 visitors to the monastery that year.

In the second half of the 20th century the abbey school began to accept girls, the monastery’s business operations were restructured, many parts of the abbey complex were adapted for guests and visitors, and the building was completely restored.